SpeeD

Speed, in music, means playing fast in a musical context. Not just playing fast. Playing in a musical context means staying coherent with the rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic content of the piece. If you play fast but ignore the musical elements, then you are just playing fast, but not using speed. Speed implies control. A child can pick up the harp for the very first time, blow or suck and flail the harmonica in front of his/her lips and play fast. But this is not musical speed, as you can tell.

Let me divide speed playing into two categories: composed and improvised. The composed category includes everything where what to be played has been worked out ahead of time. The improvisedcategory includes everything else, where what is played was not planned ahead of time.

Speed for Composed Play

Composed play is not limited to playing classical harmonica compositions.. it also includes everything from executing riffs and licks that have been learned to playing a song like “Juke” note for note.

To play something that has been already defined–there’s no getting around it, you have to play it that way (or some planned variant of that way). You have to work with your skill at the elements required for the phrases you are going to play.

Sometimes there will be certain elements: note transitions or jumps or technical difficulties that are particularly difficult to play. As you practice you will become aware of the places you have the most difficulty. These are the areas to isolate and work on individually. Practice those elements enough that you gain control of them. Practice them enough that instead of dreading them, you look forward to them because you can do them so well. Practice them enough that other elements of the music become more difficult than these, which were more difficult at first. Gaining control of these new problem elements will probably be far easier than controlling the initial elements. Keep playing the initial difficult but now not problematic elements as you practice the new less difficult but more problematic ones. This should become a process of smoothing and controlling the transitions between the different elements of the phrase(s).

Investigation of the underlying breathing patterns required to play the notes in the phrase can help in determining what you need to do to be able to execute the passage properly. Memory becomes a dominant factor when playing fast composed passages, because speed means lots of notes and rhythmic patterns, and lots of anything means lots to remember. Understanding the underlying breathing patterns gives you something besides individual notes to remember and on which to focus, making the memory task easier, as well as enhancing the ability to execute the phrase.

Start Slow

When working on passages that are to be played fast, start out working on them very slowly, paying particular attention to rhythm and tempo and dynamics. Concentrate on all the subtelties that go into the passages, note transitions, moving to different holes, head, hand, and arm movements. Exaggerate your movements smoothly while playing slowly–think of a slow ice skating performance, where the arms and hands extend and sweep in time with the music and the skating.

When you eventually move to faster speeds, you cut back on these exaggerated movements which tends to keep the note transition relative-timings fairly consistent. For example, if you are playing slowly and still require some extremely fast compact movement to play some sequence of notes, there’s no room there to speed up that part later. You need to put some exaggerated smooth and appropriate motions in your play so you know you are practicing at a speed that you will be able to improve upon later. Some parts may require more exaggerated movements than others to keep the tempo and rhythm correct. Where you are least able to exaggerate the slowness is where you will be limited on how fast you can play the passage.

Practice playing very smoothly at very slow speeds initially. Only after you get comfortable and competent playing at slow speeds should you move to faster speeds. As you start to speed things up, intermix the faster passage with the slower one in a controlled way, as a whole–don’t play a little fast and a little slow during the passage. Keep the passage smooth and in rhythm in its entirety, but play the different speed passages back to back. For example, play the passage at the speed you are comfortable with, then push yourself a little faster for the whole passage and don’t worry about missing notes. Keep going and keep the rhythmic integrity intact. Keep your dynamics and phrasing under control, and if you hit some wrong notes.. so be it, that’s okay. Then go back and play the passage at the slower speed at which you can hit all the notes comfortably with exaggerated control. If you find you can’t keep the rhythmic integrity and dynamics in place, you aren’t ready to move to a higher speed. Concentrate on those musical elements at the slower speed and get them ingrained in your aural image of the passage.

Think about relaxing, and minimizing the muscles involved in playing the passage (though the ones in action may be making extended movements). As you play slowly, work on optimizing your approach to the passage, playing smoothly and efficiently, but with a degree of motion commensurate with the speed at which you are playing.

Start with only a couple of notes, and gradually add one before or one after the small set you are working on. Slowly build up the number of notes you are playing and build up the context of the fast passages, the notes leading into the passage, the passage itself, and the notes following the passage.

Improvised Speed

Improvised speed is playing fast in a musical context where the notes you play aren’t worked out ahead of time.

Ornamentation

Ornamentation is the adding of musical ornaments to a note. A musical ornament is one or more notes leading to or from the primary note. The “primary” note is the note being ornamented.

For example, you could ornament a long held 3 draw note with a quick shake to the 4 draw and back. You could ornament a long 4 draw with a succession of 3 draw to 4 draw shakes. You could ornament the 3 draw of the shake with a 1/2 step bend. You could ornament back to back 6 draws with an evenly spaced 4-5-4 shake in between. In other words, the number of possible ornamentations is vast!

Ornamentation is taking advantage of the musical space provided by held notes and rests in the musical phrase to add notes in the rhythmic context of the underlying music.

Ornamentation should work with the flow of the music and the flow into, during, and out of a phrase.

The above principles make it clear that ornamentation is more concerned with rhythm and feel than with the exact notes to be played. These notes are short, being played quickly, and lose some of their musical significance They are ornaments, not the tree or its branches. Instead of thinking notes, ornamentation is more concerned with direction–where direction means moving toward a note, staying on the note, or moving away from a note. Or some combination of those motions. You can start with your primary note and stay there; or play notes that move ever farther away from it; or first move away from it, then back to it; or jump away from it and move steadily back to it. Or even combinations of those, changing directions more than once before returning to the primary note.

Where do you get the primary note? You either have it already because you’re ornamenting a preset phrase, lick or riff, or you pick it.

Picking Improvised Primary Notes

Primary notes should first be picked to follow or enhance the musical groove.. the overall rhythmic feel, the flow of the music. In other words, they should first be picked as to when they are played, rather than which note is played.

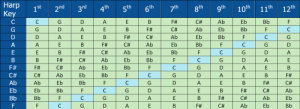

Primary notes are most often picked from the scale and mode of the music, e.g. C major or D minor or E blues. The Layout Generator can show you the notes in the scale and mode of the music for different positions.

Primary notes are most (or very) often picked from the notes in the current chordal harmony, even if that harmony contains notes not part of the basic scale.

Improvisation about a melody often will involving picking primary notes from that melody at the time the melody note would or does occur. Improvisation about a melody will often use rhythmic patternsfrom that melody with different notes, and improvisation of primary notes will often be driven by the underlying rhythmic pattern, whether it comes from a fore-known phrase or not.

Breathing Patterns

Improvised notes can also be picked by using underlying breathing patterns as the basis for note selection. During fast play, the rhythmic integrity is far more important than the particular note chosen, especially if the notes are at least in the key of the music, which is often the case for most notes on the diatonic harp we choose to play for a particular piece of music. Breathing patterns can establish a rhythmic pattern and basis for which the exact notes are less significant than the consistent rhythmic pattern. These breathing patterns and rhythms will generate notes automatically. Consider the perididdle: blow draw blow blow, draw blow draw draw. When you move to a hole while playing with that breathing pattern, you get what note is there. If you don’t move to a new hole, you still get what note is there.

One benefit to the use of breathing patterns is realized by selecting rhythmic patterns with breathe-in-breathe-out symmetry so that long lines can be played without running out of breath, in either direction.

Primary Note Phrases

Primary note phrases can be preset or composed phrases, licks and riffs, or improvised phrases that take the place of predefined ones. These phrases can be placed within the context of fast play, the fast play using ornamentation, breathing patterns, or other note selection techniques to augment the notes in the primary phrase.

In other words, a certain number of beats or bars can be allocated for speed work. Many different notes and different rhythmic patterns are used during the fast play. As part of those notes and rhythms, a higher level phrase can be superimposed to emphasize the overall musical rhythm and provide a motivated musical flow through the many short notes.

In still other words, there will be a few important musically motivated notes, and a lot of relatively unimportant notes, which are musically okay as long as they are played at the right time.

These motivated note phrases generate their own breathing patterns. Ornamentation or other quick notes can be chosen that fit with these motivated breathing patterns. This leads to fast lines that fit well with the music, the motivated phrase leading the ear through the flurry of short notes, and are relatively easy to execute since they fall naturally within the breathing patterns generated by the motivated primary note phrases.

These motivated note phrases can be treated as composed, with the fast notes added in an improvised fashion each time. This allows an improvised section of music to be played with consistent feel, if not consistent notes, and is much easier to remember than long lines of short notes played in a particular way. This can lead to music that contains elements of a composed improvisation.

General Speed Tips

Breathing

Fast passages can require rapid changes from inhaling to exhaling, and vice versa. These rapid changes are accomplished by quick movements of the diaphragm. Practice panting, like a dog pants, to help strengthen the diaphram muscle and train it to respond quickly to changing breath direction.

While you’re practicing panting, you might as well be playing chords too. Put a low key harp in your mouth and cover a chord and practice your panting so that you get the deepest, biggest, fullest chord you can. Open up your mouth and throat and hide your tongue down at the bottom of your mouth, a soldier hiding from enemy fire. Visualize an egg in there, a large egg pushing the insides of your mouth outward and your tongue down. Pant through the harp, but listen to your chords. Make them sound good. Slow down a little if you have to. Make sure all the notes sound, each one, and try to get them all sounding even. Shift to a double stroke roll–two pulses out and two pulses in. Control the pulses with your diaphragm. Slow down if you have to. Keep it going. Turn it into a train if you want. Say “hooka” when you breathe out and “tooka” when you breathe in. Say “Tah hooka tooka hooka”, with “hooka” said while breathing out, and “ta” and “tooka” said breathing in. Move the “Tah” around. Then stop articulating with your tongue–stop saying tah hooka tooka. Open your mouth back up, drop your tongue back down and just play a double stroke roll with big full chords. Keep it under control.

Don’t pant for too long or you might get dizzy.

Speed Dynamics

Use varying dynamics to emphasize the underlying groove and primary note phrases. Pulse the music so that it has a heartbeat. Remember your panting practice? Use your diaphram, that’s what you’ve been working on it for. Hit the note(s) on the beat a little harder than the rest. Hit beats 2 and 4 even harder to swing the rhythm. Emphasize notes in the primary phrase over ornamented notes or notes that come from breathing patterns. Pulse the breathing pattern rhythmically to emphasize a part of the pattern.

Playing Pressure

Control over your playing pressure is a foundational element of playing fast smoothly with good tone, whether you’re playing preset passages or improvising. Even reed response up and down the harp greatly helps playing fast passages smoothly and cleanly with consistent tone. The two most important factors in even playing response of the reeds are good compression (i.e. a good air tight harp) and correct gap height of the reed above its slot in the reedplate. Of these, the most important and most easy to address is the reed gapping. If you play commercial harps (not custom ones like those from Joe Filisko or Richard Sleigh, etc.) you should be setting your reed gaps according to your playing style. If you choose not to do so you will be at the whim of chance, and many harps will not respond the way you like.

Speed Is It’s Own Articulation. Fleeting notes don’t require the same degree of control over attack, shaping, and vibrato as slower ones. When you practice by playing fast passages slowly, take care to play with the same playing pressure, legato, staccato or other effects as you will when you finally play them fast. Don’t try to enunciate each note in a very fast passage with articulations like Ta, Ha, Da, Ka, etc. Unless you’re very practiced with triple-tonguing techniques and synchronizing your tongue with rapid-fire notes, you’re probably better off getting your tongue out of the way. Establish a playing pressure, and be able to achieve that pressure for rapid changes in breath direction.. in other words, make sure your pressure is consistent enough that you achieve the same volume inhaling and exhaling–or whatever volume is needed at the time to express the musical dynamics.

High Notes

Much if not most speed work is done on the high end of the harp. The reeds are shorter and respond faster at the high end than on the low end. Also, musically, the high notes have more energy and cut through the overall sound better than low notes. Often higher key harps are chosen for very fast work because the high notes on them can respond faster than the high notes on lower key harps. Much fast work is done on a normal (high) F harp, or even a high G because you can really fly, and the notes really cut through.

Parting Thoughts

If you’re good enough on the harp to be ready to incorporate musical speed, you are definitely ready to make the small effort required to set up your harp, and most of that is in setting the reed gaps, which is easy and not very risky to the harp. (As with anything, practice the first few times on harps that are not your favorite..)

Speed can be over used. The harp is best at shaping notes, that is its strength. Speed can add spice to the musical mix, but like cooking with spice, enough is good and too much is worse than none.

The Diatonic Scale

The Diatonic Scale That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes

That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes  C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B

C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B modal scales you played earlier. They move closer to the start note each time; until they eventually become the start note.

modal scales you played earlier. They move closer to the start note each time; until they eventually become the start note. These are ancient Greek names. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was actually part of the ancient Olympic Games. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes and came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, Doric, capitals to their columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Myxolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than an actual Greek tribe of small stature.

These are ancient Greek names. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was actually part of the ancient Olympic Games. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes and came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, Doric, capitals to their columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Myxolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than an actual Greek tribe of small stature.

As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing in

As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing in

Here’s the solution. To be empirically accurate, we need to start counting not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps only. This way the chromatic interval between

Here’s the solution. To be empirically accurate, we need to start counting not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps only. This way the chromatic interval between