What Is Tempo?

What Is Tempo? There’s a pulse that connects all music. This universal communication tool is more than just rhythm, harmony and melody-in fact, non-e of the matter without a tempo.

Tempo is one the simplest concepts to grasp in music theory, but it’s 1 of the most difficult to actually play.

Musicians will spend their entire lives attempting to play and find the tempo.

In this article let’s explore all the different ways of approaching tempo so you can master the concept in your own music.

[toc]

What Is Tempo?

Tempo is the speed at which a little bit of music is played. There are three primary techniques tempo is communicated to players: BPM, Italian terminology, and modern language.

Tempo vs. Time Signature

Since it refers to the number of beats per minute and not the amount of beats per way of measuring music, tempo is quite different from time signature.

Tempo and rhythm are intertwined and rely on each other very closely, but tempo should be thought of as the canvas or structure where rhythms exist.

You can imagine time signature as interacting with the tempo in the sense that the bottom number in enough time signature determines the pulse and the way the pulse is subdivided.

Time signatures, rhythms and syncopation are how artists take a factual, measurable number like BPM and sculpt it into musical information-essentially creating art with the fabric of time!

Tempos are sort of psychedelic when you consider it!

What Is Beats Per Minute (BPM)?

This method involves a*signing a numerical value to a tempo. “Beats per minute” (or BPM) is self-explanatory: it indicates the number of beats in a single moment. For instance, a tempo notated as 60 BPM means that a beat sounds exactly once per second. A 120 BPM tempo will be twice as fast, with two defeats per second.

In terms of musical notation, a beat almost always corresponds with the piece’s time signature.

- In a time signature with a 4 on the bottom (such as 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 5/4, etc.), a beat will correspond with quarter notes. So in a 4/4 time, every four defeats will take you through a full measure. In 5/4 time, every five beats will need you through a measure.

- In a time signature with an 8 on the bottom (such as 3/8, 6/8, or 9/8), a tempo beat typically corresponds having an eighth note.

- Sometimes tempo beats correspond with other durations. For instance, if you need to count the right path through a measure of 12/8, you could choose a tempo that represents eighth notes (where 12 tempo beats get you through one determine) or perhaps a tempo that represents dotted eighth notes (where 4 tempo beats would allow you to get through the measure).

BPM is the most precise way of indicating fast tempo or slow tempo. It’s found in applications where musical durations must be completely precise, such as film scoring. It’s also used to create metronomes that are used on the highest level professional recordings. In fact, some people utilize the term “metronome marking” to spell it out beats per minute.

What Are the Basic Tempo Markings?

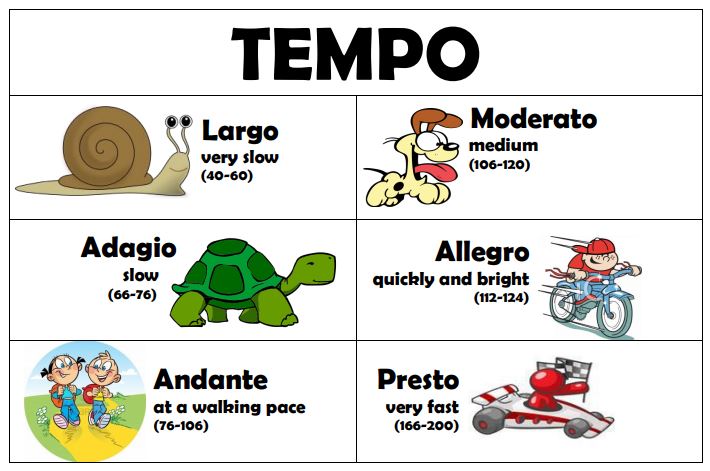

Musical terminology makes regular use of the following tempo markings:

- Larghissimo—very, very slow, almost droning (20 BPM and below)

- Grave—slow and solemn (20–40 BPM)

- Lento—slowly (40–60 BPM)

- Largo—the most commonly indicated “slow” tempo (40–60 BPM)

- Larghetto—rather broadly, and still quite slow (60–66 BPM)

- Adagio—another popular slow tempo, which translates to mean “at ease” (66–76 BPM)

- Adagietto—rather slow (70–80 BPM)

- Andante moderato—a bit slower than andante

- Andante—a popular tempo that translates as “at a walking pace” (76–108 BPM)

- Andantino—slightly faster than andante

- Moderato—moderately (108–120 BPM)

- Allegretto—moderately fast (but less so than allegro)

- Allegro moderato—moderately quick (112–124 BPM)

- Allegro—perhaps the most frequently used tempo marking (120–168 BPM, which includes the “heartbeat tempo” sweet spot)

- Vivace—lively and fast (typically around 168-176 BPM)

- Vivacissimo—very fast and lively, even faster than vivace

- Allegrissimo—very fast

- Presto—the most popular way to write “very fast” and a common tempo in fast movements of symphonies (ranges from 168–200 BPM)

- Prestissimo—extremely fast (more than 200 BPM)

How Is Tempo Used in Music?

Tempo is a key element of the musical performance. Inside a piece of music, tempo can be just as important as melody, harmony, rhythm, lyrics, and dynamics. Classical conductors use different tempos to greatly help distinguish their orchestra’s rendition of a classic item from renditions by other ensembles. However, most composers, all the way from Mozart to Pierre Boulez, provide a lot of tempo instructions in their musical scores. So when it comes to film underscore, certain tempos are crucial when setting certain moods.

One particularly notable tempo is the “heart rate tempo,” that is a musical speed that roughly aligns with the beating pulse of a human heart. Although heartrates change from person to individual, most fall in the range of 120 to 130 BPM. Analysis has shown that a disproportionate number of hit singles have already been written within this tempo range.

How to find the tempo?

Space and time aside, finding the tempo is a lot more difficult-and it’s definitely the most crucial section of understanding and using tempo.

Keeping up and playing around with that rigid, unforgiving, deterministic measure of time requires a lifeperiod of skill plus practice.

Here’s a few things to keep in mind when approaching tempo in your music.

Find a metronome

The metronome was invented in the 1800s and contains been used as a way to help musicians continue beat ever since.

Today metronomes are very easy to find when compared to classic wind-up metronomes of days past.

Your best bet would be to get an app, Google it or utilize the metronome in your DAW-which is clocked to MIDI and glues everything together.

Practice to a metronome

Practicing to a metronome mthey be the equivalent of eating your vegetables, taking vitamins and weight lifting.

It’s difficult, it takes discipline, it’s not super fun-but it will make you a much, much better musician.

Even the most seasoned professionals will turn the metronome on during their private practice sessions.

The metronome is like a mirror, it shows where all your imperfections lie also it gives you a reference point for where you can reach.

Playing to the metronome is indeed important, if you want in order to be a serious musician you need to practice to one.

When you practice with a metronome you’ll discover how difficult it really is to play at slower speeds.

A slower tempo is often very difficult for musicians to internalize because the space between beats is more pronounced.

Hot tip: If you play with a group, learn to perform your songs to a metronome at various tempos. Achieving this will provide you with a greater level of control when playing live and with out a metronome.

Look at your watch

Looking at your watch is an excellent solution to identify a tempo if you’re curious what the tempo of a song is, or desire to find the tempo before kicking off a track.

Just look at the clock and count the number of beats throughout a specific interval.

For example, if you count 40 beats during a 30-second interval the song is played at 80 BPM.

Memorize a few songs

In the movie Whiplash, the conductor asks the drummer to play a specific tempo, with the expectation that the drummer should know exactly how to kick off a song at 130 BPM.

In reality, this is not an expectation that any band leader should place on any musician.

Humans are not robots and you also can’t expect anyone to play a particular BPM on command.

But, with practice, humans are great at approximating a tempo on command.

One great way to master this skill is by memorizing the tempo and beat of a handful of memorable songs that are well-known for following a certain tempo.

Here’s a few which come to mind.

The Diatonic Scale

The Diatonic Scale That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes

That’s a thirteen note sequence. And, just in case you’re wondering, yes  C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B

C 4B 4D 5B 5D 6B 6D 7D 7B modal scales you played earlier. They move closer to the start note each time; until they eventually become the start note.

modal scales you played earlier. They move closer to the start note each time; until they eventually become the start note. These are ancient Greek names. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was actually part of the ancient Olympic Games. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes and came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, Doric, capitals to their columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Myxolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than an actual Greek tribe of small stature.

These are ancient Greek names. The Greeks recognised the science, art and magic of music. Indeed, music was actually part of the ancient Olympic Games. The Dorians were one of the four major Greek tribes and came from central Greece – they built temples with plane looking, Doric, capitals to their columns. Locrians were a minor tribe from north-west mainland Greece. Two of the other major Greek tribes were the Ionians who settled the Ionian seaboard in what is now Turkey, and the Aeolians, originally from Thessaly in mainland Greece. The Phrygian community was from Asia Minor (Turkey), as were the Lydians of Anatolia. Myxolydian means half, or almost, Lydian, and is a technical afterthought rather than an actual Greek tribe of small stature.

As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing in

As we do so, we’re probably aware that we’re playing in

Here’s the solution. To be empirically accurate, we need to start counting not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps only. This way the chromatic interval between

Here’s the solution. To be empirically accurate, we need to start counting not in diatonic intervals, but in chromatic intervals, or half steps only. This way the chromatic interval between

Close encounters of the third kind

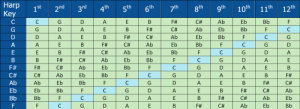

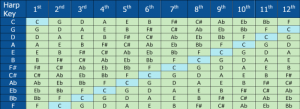

Close encounters of the third kind  So what are positions all about? In the simplest terms, we can take a C major harmonica and use it to play in different keys just by using a different hole as our root note, or starting point, each time. Some keys will be more useful than others, but in theory we could start from any natural, sharp or flat note (black or white key on the piano) and find some fun phrases. In doing so we are inadvertently working in different musical positions. By way of example, When The Saints works well from 4B, Juke works well from 2D, Summertime works well from 4D and Au Claire De La Lune is best played from 5D. To forge an answer to our original question however, we need to apply some logic and find a workable formula or DNA to explain what’s going on. Why? Because it will enable us to express ourselves as musicians rather than just harmonica players. And with this comes greater understanding and enjoyment of our instrument and music in general. The solution is where music and maths collide in the form of the circle of fifths.

So what are positions all about? In the simplest terms, we can take a C major harmonica and use it to play in different keys just by using a different hole as our root note, or starting point, each time. Some keys will be more useful than others, but in theory we could start from any natural, sharp or flat note (black or white key on the piano) and find some fun phrases. In doing so we are inadvertently working in different musical positions. By way of example, When The Saints works well from 4B, Juke works well from 2D, Summertime works well from 4D and Au Claire De La Lune is best played from 5D. To forge an answer to our original question however, we need to apply some logic and find a workable formula or DNA to explain what’s going on. Why? Because it will enable us to express ourselves as musicians rather than just harmonica players. And with this comes greater understanding and enjoyment of our instrument and music in general. The solution is where music and maths collide in the form of the circle of fifths. Thumbing a lift

Thumbing a lift Beam me up Scotty

Beam me up Scotty Now let’s move up to G from C for second position using the circle of fifths and follow the same process. To play the G major triad on the diatonic (white key only) keyboard, we’d place our thumb on G as the root note this time, our middle finger on B and our little finger on D. Once again we’d have a satisfying and complete sound. Try it by playing 2D-3D-4D together. And again we’ve used the first, third and fifth degrees (notes) of the G major scale. And that’s second position nailed. But again let’s reinforce things by playing the G major arpeggio up and down: 2D 3D 4D 6B 4D 3D 2D

Now let’s move up to G from C for second position using the circle of fifths and follow the same process. To play the G major triad on the diatonic (white key only) keyboard, we’d place our thumb on G as the root note this time, our middle finger on B and our little finger on D. Once again we’d have a satisfying and complete sound. Try it by playing 2D-3D-4D together. And again we’ve used the first, third and fifth degrees (notes) of the G major scale. And that’s second position nailed. But again let’s reinforce things by playing the G major arpeggio up and down: 2D 3D 4D 6B 4D 3D 2D into F# rather than F. But we don’t really have an F# because we’re using a diatonic keyboard remember? White keys only. F# is most definitely a black key. So we’re kind of stuck with what we’ve got.

into F# rather than F. But we don’t really have an F# because we’re using a diatonic keyboard remember? White keys only. F# is most definitely a black key. So we’re kind of stuck with what we’ve got.

G’night John Boy!

G’night John Boy!